We are celebrating Women’s History Month shortly after the election of Kamala Harris as Vice President who shattered one of the last remaining glass ceilings. In her inaugural address, she reflected on the centuries of work that came before her, saying “It is my honor to be here. To stand on the shoulders of those before me.” Today I want to highlight one of those who came before — someone whose efforts laid the groundwork for the modern human rights movement.

Eleanor Roosevelt was born into privilege, ascended to heights of power and fame, and could easily have coasted to a life of luxury and philanthropy. Instead, she chose the road less traveled, upsetting peers but changing the course of history in the process. She was willing to break protocol and make the office of the First Lady into a platform for social change. Most of all, Eleanor Roosevelt had an unwavering sense of justice for those who’d never had the privileges of her own upbringing.

Her perspective on the plight of the poor and marginalized came in part from serving as the “eyes and the ears” of her husband’s New Deal anti-poverty programs. She toured the country extensively and observed firsthand the devastation and impact of the depression on children, women, immigrants, and minorities. Eleanor’s outspokenness, her advocacy on behalf of Black Americans, and her unwillingness to be a wall-flower as First Lady upset convention and opened doors.

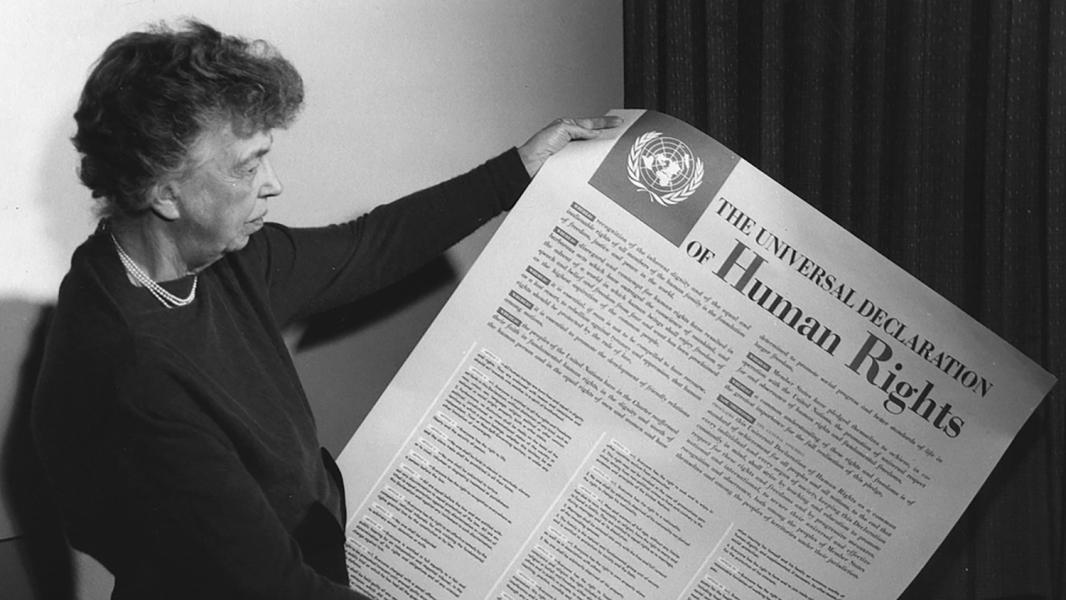

After FDR’s death, President Truman appointed her as a delegate to the United Nations, where she became the first chair of the Commission on Human Rights. There she was one of the key authors of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. A central thread of that document is that freedom doesn’t simply rest upon the rights government can’t prevent us from exercising (speaking, assembling, worshipping), but that freedom is also living without fear of hunger, exposure, illiteracy, or untreated illness.

What, you might ask, does that have to do with the Port of Seattle? The COVID-19 pandemic is disproportionately impacting women, youth, limited English speakers, and BIPOC communities — the same populations living near Port facilities and working in Port-related industries like aviation and maritime. And here is the key insight: as the Port seeks to contribute to regional economic recovery, our efforts are best applied to those most at risk of losing shelter, food, healthcare and education. Since last May, we have been working to safely maximize our partnerships and operations to connect the maximum number of people to those basic needs.

In response to the pandemic, the Port partnered with four local non-profit organizations — Seattle Goodwill, Partners in Employment, Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle, and Seattle Parks Foundation — to provide youths of color and low-income youths with professional training and short-term employment opportunities in 2020. The program provided nearly 200 youth with paid learning opportunities designed to build skills to succeed in the workplace, create learning opportunities that connect young people to a long-term career path in a port-related industry, strengthen community, and support young people and their families.

On February 9th we expanded our commitment to equitable recovery when the Commission authorized nearly $1 million in Port Economic Recovery Grants and $200,000 in Port Environment Projects grants to two dozen South King County Organizations serving some of the communities hardest hit by COVID-19.

Eleanor Roosevelt understood that freedom means not simply the right to speak one’s mind or meet with those you so choose, but also the right to basic needs like food, shelter, healthcare, and education. As we emerge from a time of crisis, when so many in our community have felt fear over meeting their basic needs, every organization can play a unique role in connecting people to something even better than a recovery. We are committed to an economy built on shared prosperity and access to opportunities for all.

Primary photo: Eleanor Roosevelt and Edith Sampson at United Nations in New York, September 1950. Photo courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.